Operant Conditioning: An In-depth Analysis

Introduction

Have you ever wondered why your cat knows exactly what it means when you pull out the trimmer? Or your dog does that adorable little dance, tail wagging and all, when you reach for the treat jar?

Well, we give you one word: conditioning. It's not some spooky mind-control tactic (though it can feel that way sometimes), but rather a fundamental way we all learn and adapt to the world around us.

Think of it as the universe saying, "Hey, that thing you just did? Good job! Here's a cookie (or maybe just the feeling of satisfaction). Do it again!" Or, conversely, "Welp! That didn't quite work out. Maybe try something different next time?"

In today's blog, we will explore and dissect every single corner of conditioning, specifically operant conditioning and how it touches every part of our lives. But before that…

What in the World is Conditioning Anyway?

Before we dive headfirst into the "operant" part, let's understand the broader concept of conditioning. Think of it as learning through association. There are two main types you might have heard of:

Classical Conditioning (Pavlovian Conditioning):

This is the OG of conditioning, made famous by good ol' Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, and his puppies.

Remember the bell that made the dogs salivate even without food? That's classical conditioning in action!

It's more about involuntary responses being linked to new triggers. And the one thing it failed to address was the complexities of human nature, as it never explored our cognitive processes and human agency.

Operant Conditioning:

This type of learning focuses on how the consequences influence our voluntary behaviours. It's all about action and reaction. If you do something and get a reward, you're more likely to do it again. If you do something and get a punishment, you're less likely to repeat it. Simple, right? But the nuances are where the magic (and the potential for mischief) lies.

So, while classical conditioning is about associating stimuli, operant conditioning associates behaviours with their outcomes. Classical conditioning is about what happens to you, while operant conditioning is about what happens because of your actions.

The Five Principles of Operant Conditioning

If operant conditioning were just about rewards and punishments, we wouldn't be here writing a whole blog about it. Much like anything to do with humans, it has certain layers that must be peeled open to fully understand it. Here are the five key principles that form its foundation:

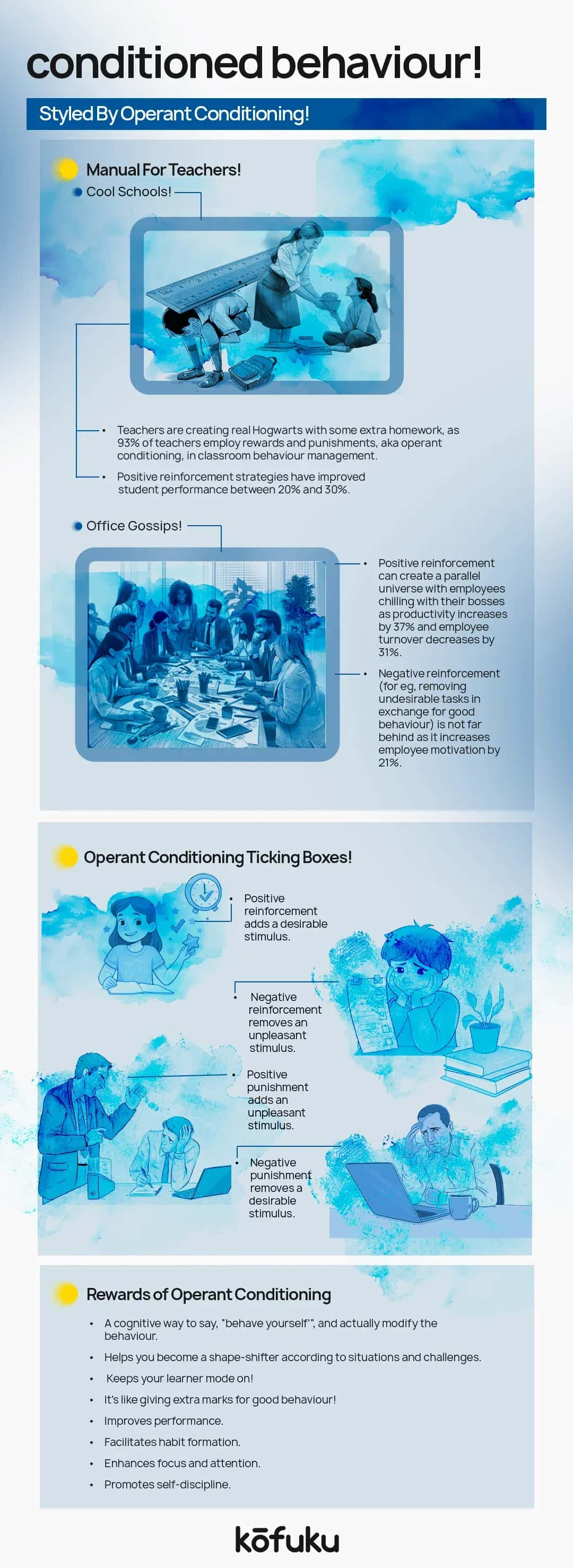

Positive Reinforcement

This is probably what comes to mind first when you think of rewards. Positive reinforcement involves adding something desirable after a behaviour occurs, making that behaviour more likely to happen again in the future.

Think of a child getting a cool sticker of their favourite character for completing their homework, an employee receiving a bonus for exceeding their sales targets, or even a simple "good job!" from a friend.

The key is that the added stimulus is something the individual finds rewarding. According to a 2003 study published in the Journal of Organizational Behavior Management by Stajkovic & Luthans, positive reinforcement is a powerful tool for improving employee performance and motivation.

Negative Reinforcement

Now, don't let the word "negative" fool you. Negative reinforcement isn't about punishment. Instead, it involves removing something unpleasant after a behaviour occurs, also making that behaviour more likely to happen again.

Imagine hitting the snooze button to stop that annoying alarm, taking an antacid to get rid of heartburn, or a student handing in an assignment to avoid a late penalty.

In each case, a negative stimulus is removed, reinforcing the behaviour that led to its removal. It's about escaping or avoiding something undesirable.

Positive Punishment

Positive punishment involves adding something unpleasant after a behaviour occurs, making that behaviour less likely to happen again. For example, a child touching a hot stove and getting burned, or a driver receiving a speeding ticket. The added stimulus is aversive and aims to decrease the likelihood of the behaviour repeating.

Negative Punishment or Omission Training

This involves removing something desirable after a behaviour occurs, making that behaviour less likely to happen again.

Imagine a teenager losing their phone privileges for breaking curfew, a child having their favourite toy taken away for roughhousing their sibling, or an employee losing a perk for consistently being late.

Removing something valued aims to reduce the occurrence of undesirable behaviour.

Extinction

This happens when a previously reinforced behaviour is no longer followed by any reinforcement (positive or negative). Over time, the individual is made to pursue a different method to achieve the desired result.

Think of a child who used to throw tantrums to get attention. If their parents consistently ignore the tantrums, the behaviour will likely extinguish because it no longer yields the desired outcome.

However, be warned: extinction can sometimes lead to an "extinction burst," where the behaviour temporarily increases in intensity before finally fading away – like a toddler throwing an even bigger tantrum to see if it still works!

The Multiverse of Operant Conditioning Theories

Much like Pavlov’s study and the subsequent theory on classical conditioning, Operant conditioning didn't just pop out of thin air. Several brilliant minds have contributed to its development and refinement.

Edward Thorndike was often considered the grandfather of operant conditioning. His famous "puzzle box" experiments with cats laid the groundwork for the field.

He observed that behaviours followed by satisfying consequences were more likely to be repeated, while those followed by unpleasant consequences were less likely to occur. This observation became known as the Law of Effect, a cornerstone of operant conditioning.

Burrhus Frederic Skinner is arguably the next most influential contributor in the evolution of operant conditioning. He formalised many of the concepts we've discussed, conducted extensive research using his famous "Skinner box," and emphasised the importance of environmental consequences in shaping behaviour.

Skinner believed that all behaviour could be explained by learning principles, famously stating, "Give me a child and I'll shape him into anything." While this radical behaviourism has given him much heat, his contributions to understanding reinforcement schedules and shaping are still undeniable.

Albert Bandura might not strictly be an operant conditioning theorist, but his Social Learning Theory (later renamed Social Cognitive Theory) significantly broadened our understanding of how we learn.

He emphasised the role of observation, imitation, and cognitive processes in learning, suggesting that we don't just learn through direct experience with consequences but also by watching others.

His famous Bobo doll experiment demonstrated the power of observational learning, adding a much needed social dimension to the behaviourist perspective.

Beyond just the main guys, many other researchers have contributed to our understanding of operant conditioning, exploring topics like different schedules of reinforcement (fixed ratio, variable ratio, fixed interval, variable interval), the role of motivation, and the application of these principles in various settings.

Operant Conditioning in the Real World

You might be surprised to learn just how deeply operant conditioning is woven into the fabric of our daily lives. It's not just for training pets or conducting lab experiments; it shapes our behaviour in countless ways, often without us even realising it. For example:

Education

Grades (positive reinforcement for good performance, negative reinforcement for avoiding failure), being made to stay back after school (positive punishment), taking away snack breaks (negative punishment), praise from teachers (positive reinforcement), and even the satisfaction of understanding a difficult concept (intrinsic positive reinforcement) all play a role in shaping a students' learning behaviours. The system is literally designed to optimise this concept and use it to condition students.

Workplace

After the learning phase is over, promotions, bonuses, recognition, and praise once again act as positive reinforcers for desired work behaviours. Conversely, demotions, pay cuts, and reprimands serve as positive punishments.

Deadlines can act as negative reinforcers since completing the task removes the pressure. According to a 2016 Gallup poll, employees who receive regular recognition and praise are more productive and engaged.

Parenting

From rewarding good behaviour with treats or privileges to implementing time-outs for misbehaviour, parents constantly use principles of operant conditioning (sometimes intuitively, sometimes intentionally) to guide their children's development.

Behavioural Therapists

Behavioural therapies, like Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), heavily rely on operant conditioning principles to help individuals with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental conditions learn new skills and reduce challenging behaviours.

Token economies, where individuals earn tokens for desired behaviours that can be exchanged for rewards, are a common application.

Marketing and Advertising

The loyalty programs that reward repeat purchases (positive reinforcement) or advertisements that highlight the negative consequences of not using a product (subtle negative reinforcement) are all great examples of operant conditioning.

Marketers are masters at understanding what motivates behaviour, and so they use it to tactically coerce desired outcome.

What Does It All Mean?

If you've reached this far, you must have a niggling feeling that maybe operant conditioning is scarily manipulative afterall.

The principles of this conditioning also open up some trippy philosophical questions.

Does our understanding of how external consequences shape behaviour challenge our notions of free will? If our actions are largely a result of reinforcement histories, how much control do we truly have?

Behaviourists like Skinner argued that free will is an illusion, and that environmental factors ultimately determine our behaviour.

This deterministic view has been met with considerable debate. Many argue that while our environment undoubtedly influences us, we still possess the capacity for conscious decision-making. Many rebel against Skinner’s theory with a little thing called human agency.

It also brings forth the complex interplay between nature and nurture. While our biological predispositions play a role, operant conditioning demonstrates the powerful impact of learning and experience in shaping who we become and how we behave.

It forces us to consider the extent to which we are products of our environments and the degree to which we can actively shape our own destinies.

The Pros and the Cons of Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning can be a powerful force for good, but like any tool, it can also be misused.

Conclusion

Conditioning, by itself, is most often instinctive. But It's interesting enough to be a worthy addition in the nature vs nurture debate.

It is undoubtedly a powerful and pervasive force shaping our behaviour and the behaviour of those around us. But by understanding its potential for both good and ill, we can use operant conditioning in a productive way while still not trampling all over our morals and principles.

While the idea of being "conditioned" might sound a bit robotic at first, remember that we are also active agents in this process. We make choices, we interpret consequences, and we learn and adapt. Operant conditioning provides a framework for understanding how those choices and consequences interact to shape our journey through life.

So, the next time you see someone (or yourself) responding to a reward or trying to avoid a negative outcome, take a moment to sit with the subtle yet profound power of operant conditioning in action. It's a reminder that the universe, in its own way, is constantly teaching us, one consequence at a time. Now, go forth and use this knowledge wisely – and maybe give yourself a little treat for making it to the end of this blog!

FAQs

Q. What is the difference between operant and classical conditioning?

A. Operant conditioning focuses on voluntary behaviours and their consequences, while classical conditioning is about associating involuntary responses with new stimuli.

Q. Is operant conditioning the same as manipulation?

A. Not exactly. While it can be used manipulatively, operant conditioning is simply a learning process. Its ethical implications depend on how and why it's applied.

Q. How is operant conditioning used in everyday life?

A. From parenting techniques and school systems to workplace rewards and marketing tactics, operant conditioning influences daily behaviour more than we realize.

Q. Who developed the theory of operant conditioning?

A. B.F. Skinner is most famously associated with operant conditioning, though it builds on earlier work by Edward Thorndike and others.

Q. Can operant conditioning be harmful?

A. Yes, if misused. Excessive punishment or manipulative reinforcement can lead to anxiety, dependency, or unethical outcomes.