Why Is Malaria So Hard to Contain in India?

Introduction

Why are mosquitoes still around? We’ve landed on the moon, invented Tinder, and done many other miscellaneous things, some of which are more useful than others. But mosquitoes? Where do they fit in the scheme of things?

Who is going to win this evolutionary war? More like an evolutionary truce, where they come, suck and we compromise.

No really. After millions of years, you’d think we’d have figured out how to evict these tiny parasites from our homes and Airbnbs. But no. Sit in a room without a fan or an AC and it's open season, “All You Can Eat: Human Buffet”. Suddenly, you’re donating blood like it’s a charity drive that you haven’t signed up for.

Forget tigers, sharks or bears. The deadliest animal on the planet weighs less than a needle and is a flying needle with wings. And they will always find your exposed ankle like it owes them money.

History of Malaria Around the World

Malaria occupies an interesting place in the annals of history. Over time, it affected Neolithic dwellers, early Chinese and Greeks, and the rich and the poor. In the 20th century alone, malaria claimed between 150 million and 300 million lives.

Today, its primary victims are people with low incomes in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, the Amazon basin and other tropical regions. 40% of the world’s population still dwells in areas where malaria is transmitted.

You’ll find ancient writings and artefacts that testify to malaria’s long rule. In India, scriptures of the Vedic period (1500 to 800 BC) termed malaria the “king of diseases.” Homer mentioned malaria in The Iliad, as did Aristotle, Plato, Sophocles, and your friendly neighbourhood physician.

It wasn’t until malaria arrived in Rome that the party started. You could call it a turning point in European history. From the African rain forest, sneaking down the Nile to the Mediterranean, spreading east to the Fertile Crescent and north to Greece. Greek traders brought it to Italy; from there, Roman soldiers and merchants would carry it as far north as England.

For the next 2000 years, wherever there were crowded settlements and stagnant water, malaria flourished, rendering people seriously ill and chronically weak and apathetic. According to historians, falciparum malaria contributed to the fall of Rome.

Malaria ravaged the population, causing many to abandon their fields and villages. The Romans suffered, as if it were a prelude for the rest of the world.

Thanks to population growth in India, people settled in semitropical southern zones that favoured malaria. Our oldest settled region was the relatively dry Indus Valley. Whoever visited or settled in the hot, wet Ganges valley to the south was plagued by this disease and other illnesses as well.

Could America be left far behind, with the rest of the world affected? Vivax malaria came with the earliest immigrants who arrived via the Bering Strait. European explorers, colonists and conquistadores carried Plasmodium malariae and P vivax as microscopic cargo.

Falciparum malaria came via enslaved people. Deforestation and “wet” agriculture brought Anopheles mosquitoes. By 1750, malaria was pretty common in America.

Presidents and Civil War soldiers fell victim to the hundreds of thousands. It was only when the Tennessee Valley Authority brought hydroelectric power and modernisation to the rural South in the 1930s that malaria stopped draining the region's physical and economic health

Just as the US was getting rid of the last indigenous pockets of infection, malaria broke out during World War II. More soldiers died because of malaria than because of the war.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the premier public health agency in the US, was founded in response to malaria.

By the time the Vietnam War came, American soldiers were just finding out that there was drug-resistant malaria in Southeast Asia.

In recent times, thanks to climate, ecology and poverty, sub-Saharan Africa has been home to around 80 to 90% of the world’s malaria cases and deaths. However, some say that resurgent malaria in southern Asia is already changing that proportion.

Why Is It Difficult to Contain in India?

Malaria is still a huge health concern and socio-economic challenge in India, contributing to a significant share of Southeast Asia’s malaria burden.

According to reports, around two million confirmed cases and 1000 deaths annually, WHO estimates indicate that the actual toll might be way worse - around 15 million cases and 20,000 deaths.

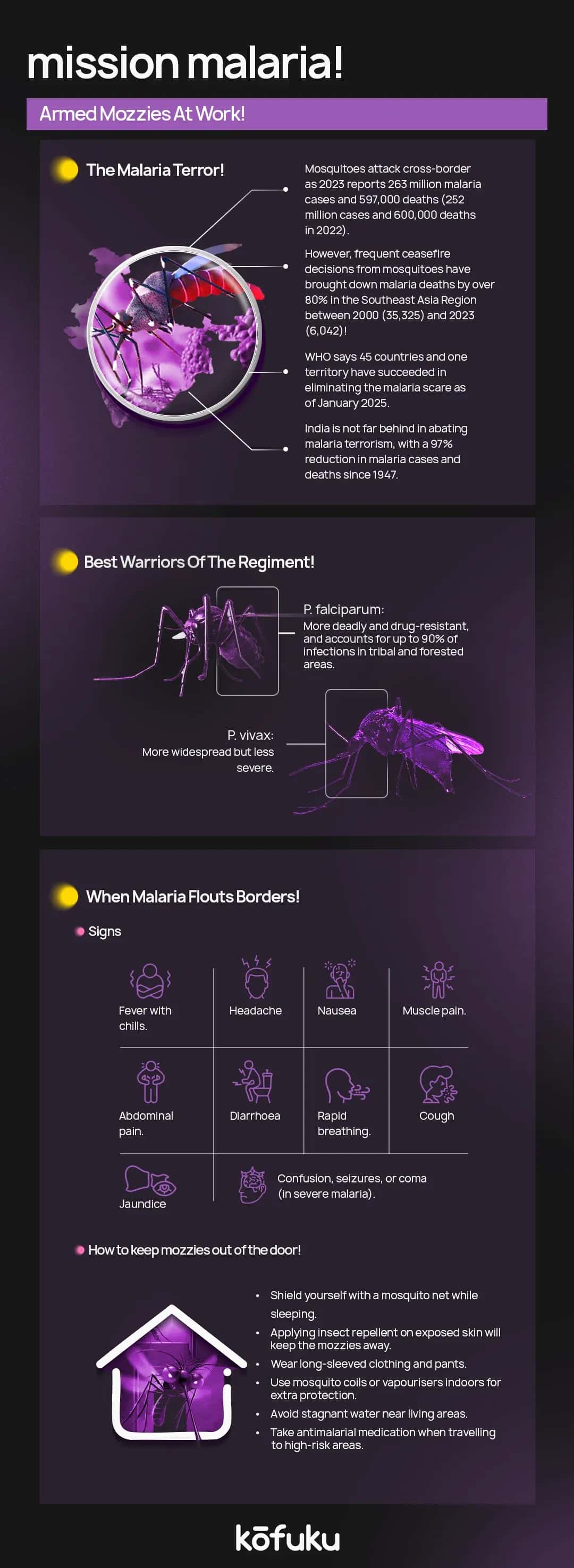

Malaria is transmitted through nine species of Anopheles mosquitoes, and both P. falciparum and P. vivax are prevalent in the country. P. falciparum is more common in forested regions inhabited by tribal communities, where it makes up around 90% of cases, and is often resistant to first-line antimalarial drugs such as chloroquine.

Complicated malaria, including multi-organ dysfunction and severe outcomes in pregnancy, like anaemia, stillbirth and maternal mortality, adds to the impact of the disease.

While the incidence of malaria fell significantly during the eradication efforts in the 1960s, it rose again in the 1970s and has since stabilised at high levels, with states like Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand bearing the highest burden.

India’s response to malaria includes a three-tier public healthcare system and the National Vector Borne Disease Control Program (NVBDCP), which emphasises early detection, treatment, community education, and vector control.

Climate variability plays a vital role. Warmer temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns can create favourable breeding grounds for mosquitoes, allowing malaria to spread to newer regions or re-emerge in areas once under control.

However, drug resistance, especially in the P. falciparum variety and underreporting in rural and tribal areas, remain significant obstacles.

Despite such challenges, economic analyses suggest that investments in malaria control are highly cost-effective, with significant returns in terms of reduced disease burden and improved productivity, especially among the working-age populations.

Studies have shown that reducing malaria leads to tangible economic benefits, especially by improving health and productivity in working-age populations.

Increasing surveillance, expanding access to diagnostic tests and treatments, integrating tribal health services, and investing in new vector control technologies could be necessary steps towards eliminating the infectious disease from India.

What Can We Do to Reduce Malaria-Related Deaths?

Though once almost eradicated, malaria resurged in India during the late 1970s and continues to be a significant public health and economic burden, especially among the rural poor with limited healthcare access.

It causes severe illness, maternal deaths, stillbirths and low birth weight, particularly impacting young children, pregnant women and anyone with low immunity.

The worst strain, Plasmodium falciparum, has been on the rise since the 1980s and accounts for almost all malaria-related deaths.

One of the biggest challenges is underreporting. The government recorded 1.5 million malaria cases in 2009, half of which were caused by P. falciparum. According to estimates, the actual number could be anywhere between 60 and 75 million annually.

Many patients bypass public health facilities and use private healthcare, where cases are often unrecorded. Malaria is most widespread in remote, underserved tribal districts like Odisha, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, making diagnosis and timely treatment difficult.

The government hasn’t been sitting idle, however. The focus has shifted from eradication to control, with stress on prevention, early detection, and effective treatment.

The introduction of Long-Lasting Insecticide-treated Nets (LLINS), Rapid Diagnostic Kits (RDKS), and Artemisinin-based Combination Therapy (ACT) has helped improve outcomes.

Community health workers (ASHAS), trained to administer tests and medication, also play an important role in last-mile healthcare delivery.

The policy of presumptive chloroquine treatment has been abandoned, as it contributed to drug resistance and rising cases. All suspected patients should be tested before treatment. Rapid diagnostic kits are the best alternative in areas where lab access is limited.

Government partnerships with private healthcare providers, including pharmacies and non-licensed practitioners, are essential to ensure nationwide adherence to testing and treatment standards.

Finally, the World Bank has stepped in to support India’s malaria efforts through programs focusing on community engagement, better service delivery, and outcome tracking.

Ongoing investment in these strategies, together with targeted vector control, public awareness, and integrating private players, can greatly reduce malaria-related deaths, especially in high-hurden and hard-to-reach areas.

Conclusion

Malaria has to be one of our country’s most persistent health challenges, thriving at the intersection of poverty, access gaps and climate.

Despite being preventable and treatable, the disease still claims lives, especially among the rural poor and tribal communities that have limited healthcare access.

The twin threat of Plasmodium falciparum and P vivax, combined with drug resistance and underreporting, makes eradication an uphill task.

There is some progress, though. Strategic interventions—like the use of Long-Lasting Insecticide-treated Nets (LLINS), Rapid Diagnostic Kits (RDKS), and Artemisinin-based Combination Therapy (ACT)—have strengthened India’s malaria control efforts.

There are challenges, however. Climate change is not doing anyone any favours—constantly expanding mosquito breeding zones, while weak surveillance and fragmented healthcare systems slow down response.

Malaria may have existed for aeons, but our future doesn’t have to include it. With sustained political will, grassroots participation, and scientific innovation, India has the tools to turn it all around. The battle is long, but not unwinnable. Until then, keep spraying that Baygon.

FAQs

Q. Why is malaria still a big problem in India despite medical advancements?

A. Malaria thrives in India due to a mix of factors—favourable climate, stagnant water, poor sanitation, population density, underreporting, and drug resistance.

Q. Why can’t we just get rid of mosquitoes once and for all?

A. Mosquitoes breed quickly, adapt to control methods, and thrive in warm, wet environments.

Q. What’s the deadliest type of malaria in India?

A. Plasmodium falciparum takes the crown—and not in a good way. It causes severe illness, drug-resistant infections, and nearly all malaria-related deaths in India.

Q. How can I personally help prevent malaria?

- Use Long-Lasting Insecticide-treated Nets (LLINS)

- Get rid of stagnant water near your home

- Use mosquito repellents and screens

- If you feel unwell, get tested immediately—don’t self-medicate

Q. Is India doing anything significant to fight malaria?

A. India has ramped up efforts through government programs like the National Vector Borne Disease Control Program, which focuses on early diagnosis, treatment, community awareness, and vector control.